- Home

- Frieda Wishinsky

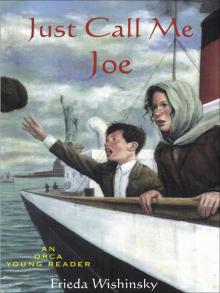

Just Call Me Joe Page 3

Just Call Me Joe Read online

Page 3

“My boss is a tyrant, just like the Czar back in Russia,” she told Joe. “He forces us to work faster and faster and if we spend more than five minutes in the bathroom, he screams we are wasting time and threatens to reduce our already small pay. Is this what we left Russia for? Endless work and little to show for it but tired bones. I want to go home to Mama and Papa. There’s no gold in New York, just misery.”

“But Anna, it’s just the beginning,” said Joseph. “It will get better.”

“When?” asked Anna. “When?” and Joseph had no answer.

Chapter Eight

Uptown

Joe felt like a thief sneaking out of the house to meet Sam. He knew Anna would be upset that he was skipping school. She’d remind him how heart-broken Mama and Papa would be. She’d tell him how important it was to go to school and learn. But he’d only skip school for one day. One day to see what lay beyond Rivington and Delancey. One day to go somewhere special.

He wished he hadn’t told Anna about his new name last night. He knew she was determined to write Mama and Papa about returning to Russia and when he said, “Don’t call me Joseph anymore. Call me Joe,” she’d burst into tears.

“See how this terrible place has changed you?” she’d cried. “You speak English all the time and hardly any Yiddish. And now you want to change your name. Mama and Papa gave you the name Joseph and now you want to throw it away like an old hat. You are not the same Joseph who left home but a hoodlum who plays on the street with other hoodlums. Oh, how I hate this New York.”

“I’m not a hoodlum,” Joe had shouted back. “And I like New York!” Then he’d run to his room only to be greeted by a monstrous snore from the sleeping Mr. Plucknik.

Joe sat on his bed watching Mr. Plucknik’s enormous hairy chest rise and fall like a stormy ocean wave and for a minute, even Joe wished he was back with his parents in Russia.

But that was yesterday, Joe told himself. Today the sun warmed his face. Today there was no Mr. Plucknik or Anna to make him feel terrible. Today he was going to have a great adventure.

“Ready?” said Sam.

“Ready,” said Joe.

“Then let’s go!”

“But I have no money for tickets,” said Joe.

“You don’t need money. Just do as I do and move fast,” said Sam.

The boys walked past the crowds of people and pushcarts on Rivington Street to the el, the train that traveled above the street.

“Make yourself invisible,” whispered Sam. Joe followed Sam’s lead as he melted into the crush of people at the station. Soon they snuck on the train without paying.

“But why did we go downtown?” asked Joe, as they ran off the el.

“To get to the subway on Canal Street. Then from there it’s uptown to 59th street and the park. And here it is — The Subway!” Sam announced it, as if they’d reached the entrance to a new world.

And it was a new world. An underground world of wooden ticket booths, glistening tiles and graceful columns. But most of all it was a world where trains rumbled through dark, mysterious tunnels deep in the belly of the city.

“Remember, invisible!” whispered Sam as he led Joe into the thick of the crowd. And somehow, again, they squeezed onto the train without paying a cent.

As the train zoomed through the tunnels, Joe and Sam pressed their faces to the windows, trying to catch a glimpse of what lay on the tracks but it was too dark to see anything but shadows.

“Next stop, 59th street!” Sam sang like a conductor.

Joe’s heart raced with excitement. Uptown! Soon he’d see it. Soon he’d stroll around Uptown streets like a rich man. In America you could do that!

And Uptown was as wonderful as Joe imagined. Mansions lined wide streets. Men in dark suits and bowler hats hurried to work. Women in taffeta and velvet with large flowered hats strolled and shopped.

It was so different from Rivington Street. Here there was room to breathe. Here there was space to walk. And beyond each carved wooden door, Joseph pictured sumptuous breakfasts of fresh eggs, warm bread, hot coffee, rich cream, all being served in endless quantity.

Joe wished he could describe it to Anna, but he couldn’t, of course. He even wished he could tell Miss Williams, who always took time to compliment him on his improving English. But there was no way he could tell hereither. He already had to make up a story about missing school.

Still it was fun to be away from school. It was good to be away from the back wall at recess beside Avram. It was good not to face those boys who wouldn’t let him play.

But what was he going to do about tomorrow? Sam wanted to take him to Central Park tomorrow. “We’ll climb rocks like explorers and watch the skaters twirl on the lake. Central Park is like your woods behind the shtetl. You’ll love it,” Sam said.

Sam was right. Joe loved the woods. Until the day the Russian soldier had almost killed him, the woods had been his favorite place. He used to take a chunk of bread and sit on a log in the woods, imagining Anna’s hairy creatures hiding in the trees. He’d listen to birds and watch rabbits and squirrels scurrying around. He’d throw pebbles into the small brook and watch them dance across the water. Sometimes he’d even catch a small fish.

But from the day the soldier threatened him, Joe never went to the woods again. He only dreamed about it. And now he had a chance to explore New York woods in Central Park, all only a subway ride away.

He had to go there. At least once.

“I’ll be here on the stoop waiting in the morning,” said Sam.

Joe ran up the steps to his building. He could smell chicken soup in the hall and on the stairs. It was coming from their apartment. He hoped Aunt Sophie had made the soup with kreplach, meat and onions wrapped in dough. One thing for sure about Aunt Sophie, she could turn a little meat and onions into magic.

Hurrah! Aunt Sophie had made kreplach! “So how was school today?” asked Aunt Sophie, as she puttered in the kitchen. “How is your English? Are you listening to the teacher?”

“Everything’s fine,” said Joe. “And my English is getting better each day.”

“Good,” said Aunt Sophie. “Your parents would be happy to know you are working hard at school.” Then she yammered on about the price of chicken and beef and how much her feet hurt from so much walking to get the best prices. “If you don’t watch those butchers, they rob you blind,” she lamented.

Joe nodded. It was always about money.

“I’m totally worn out,” said Aunt Sophie. “I’m going to sleep early. Wash up, Joseph, and then get some sleep too. A growing boy like you needs rest.”

Joe went to his room. As usual, Mr. Plucknik was asleep early and, as usual, he was snoring like thunder. For a long time, Joe lay on his bed imagining Central Park. Then he heard the click of shoes on the floor. Anna was home. Suddenly, he heard glass shatter and then the sound of sobs coming from the kitchen.

Joe slipped out of bed. Anna was picking up broken shards of glass from the linoleum floor. Tears were dribbling down her cheeks and her face was red from crying. Joe leaned over to help.

“Thank you,” said Anna in a choked voice. “I don’t know how it happened. The cup just fell out of my hand. It’s been such a terrible day and now, on top of everything, I have to buy Aunt Sophie a new cup. I barely have enough money to pay our rent.”

“Maybe she’ll understand and not ask you to pay,” said Joe.

“Aunt Sophie?” Anna said sniffing. “You know how she is about money and I can’t blame her. It is so hard to have enough money to live in New York. But it’s more than that. My friend Lucy was fired today. The boss complained that she takes too long to finish her work. I tried to explain that Lucy takes care of her old grandmother and two young sisters. I tried to tell him that Lucy is a good worker but sometimes she is a little tired after helping her family. But the boss just gave me an angry stare and yelled at me to be quiet and not interfere in what I don’t know. Then he told Lucy to pack up and leave. Lucy grabbed my hand and wh

ispered, “Thank you for trying to help,” and then she walked out.

“She’ll find another job. I heard they are always looking for workers,” said Joe.

“But all the bosses are the same in all the factories. I hate them. Today it’s Lucy. Tomorrow it could be me or someone else. They treat us like the slaves. When I helped Mama and Papa with their work, they treated me with respect. I miss them. I want to go back to Russia.”

“But Russia is full of Cossacks, Anna,” said Joe. “Remember what they did to our cousins? Remember what almost happened to me? And remember, Mama and Papa want to come to America too. ”

“It may take years for them to save enough money and meanwhile, I will be too tired and sick to care about anything. There is no hope for a future here.”

“But . . . but,” protested Joe.

“Go to sleep, Joseph,” Anna said. “It is no use to talk any more. I am too weary for words. Tomorrow it all starts again. The work. The bosses, the orders and this time I will be working without my dear friend, Lucy, by my side. You don’t know how much it helped to share a smile with her and now even that small pleasure is gone.”

Anna lifted herself wearily from the chair and stumbled into the dark room she shared with Aunt Sophie.

Back in his bed, Joe lay awake thinking.

“If I have to leave New York, I have to see Central Park before I go. I just have to.”

Then Joe fell asleep, dreaming of forests and tiny, magical creatures who lived in the heart of trees.

Chapter Nine

The Park

“Hey! Where do you think you two are going?” shouted the man in the ticket booth as Joe and Sam skittered past him onto the El.

Joe and Sam didn’t respond but squeezed themselves into the crowd of workers. Luckily the platform was so full of people and noise, the shouts from the man in the booth were drowned out.

But it was close. Joe heart beat wildly under his shirt. He was sure the woman beside him could hear it pound too.

“Phew,” he whispered to Sam, when the train finally began to move.

“You think that was close,” said Sam. “Once a ticket booth man grabbed me by my hair and yanked me off the platform. When he wasn’t looking, I snuck back on. It’s all part of the fun. Look Joe, the sun is coming out. Wait till you see Central Park in the sun. You’ll love it.”

Sam was right. Snow sparkled on the trees like lace on a dress as they walked to the lake. They stood at the edge of the frozen lake watching skaters glide on the ice. Some were as graceful as dancers but others stumbled and fell like clowns.

“I wish I had skates,” said Joe.

“Not me,” said Sam. “You could break a bone or something on that ice. I just like to watch. But come on, I want to show you my favorite place.”

Joe followed Sam deeper and deeper into the park. There were few people in this part of the park. It was quiet and peaceful like the woods. Joe felt far away from the bustle and noise of the city.

“Here we are,” said Sam, pointing to a group of jagged, large boulders. “From the top you can see all of Manhattan. Come on.”

The rocks were slippery with snow but the boys soon clambered to the top. And just as Sam said, they could see far across the city. The buildings in the distance glistened like jewels.

For a minute Joe closed his eyes, imagining the rocks in spring and summer. What a perfect spot to bring a chunk of bread, listen to birds and watch squirrels.

There was nobody to bother them here. No one to chase them away. Central Park belonged to them as well as to an yone in New York. But when Joe opened his eyes, two older boys were climbing the rocks. Both were tall and as burly and muscular as boxers. They scowled at Joe and Sam when they reached the top.

“Get out of here,” one barked at them. “These are our rocks.”

“These rocks don’t belong to anyone,” said Sam.

“They’re ours. We’ve claimed them,” snarled the other boy.

“Come on,” said Joe, in a friendly voice. “We can all share the rocks.”

But Joe’s friendly gesture only seemed to anger the boys more. “Get off or we’ll throw you off,” they shouted. Then the tallest boy shoved Joe so hard, he fell on his knees against a sharp rock. The rock cut through his pants like a knife.

“S . . . Sam!” Joe called, but there was no answer. Despite the searing pain in his legs, Joe quickly steadied himself and scuttled off the rocks. As he ran, he scanned the surrounding bushes, trees and path for Sam, but he couldn’t see him anywhere. Where was he?

There was no time now to think about it. He had to get out of this part of the park but which way should he go? Joe took a deep breath, desperately trying to decide which way to go, when he heard a voice.

“Psst . . .” it said.

Joe looked up. A figure was hiding behind a bush. It was Sam!

“Where were you?” asked Joe. “Those two almost made me break my neck.”

“There was no point in both of us getting hurt,” said Sam.

“But you left me. I don’t know my way around the park.”

“Don’t make such a big deal about it. You’re fine, aren’t you? I knew you could handle yourself. See. No harm done.”

Joe didn’t know what to say. His heart was still pounding. His leg was still throbbing. How could Sam leave him to face those boys alone?

“Come on,” said Sam, smiling as if nothing had happened. “Are you hungry?”

Joe sighed. What could he do? Maybe Sam didn’t really mean to put him in danger. “I’m starved,” said Joe, “but I don’t have a cent.”

“You don’t need a cent. I told you, in New York you can always find a way to get some money. Watch me and learn.”

Sam and Joe passed a bench. A well-dressed older man was napping on the bench. Sam quietly approached him and smoothly lifted his wallet from his coat pocket. Joe knew from Sam’s swift, sure movements that Sam had lifted wallets before.

“One dollar!” Sam whispered as he emptied the man’s soft leather wallet. “See? It’s not hard. Your turn next.”

“I can’t,” said Joe.

“What’s the matter with you? Look at this man’s expensive clothes. He won’t miss the money. You’re not in the shtetl any more, Joe. Let’s eat something and then maybe you’ll get smart.”

“I’m not that hungry any more,” said Joe.

“Well I am,” said Sam. “So let’s go.”

Joe followed Sam out of the park. Sam made everything sound so reasonable even things Joe knew were wrong. Joe knew what his father would say. “Have you forgotten everything we taught you?” He could almost see the look of disappointment in his father’s tired eyes as Sam led them out of the park and down a side street.

Joe followed Sam into the warmth of a small bakery. The intoxicating aroma of freshly baked bread hit Joe’s nose like perfume. Joe’s stomach growled as he eyed the breads, cookies and cakes neatly arranged behind glass.

“Not hungry, my foot,” said Sam. “You’d love some nice warm bread. Come on. Tell the truth.”

“You’re right,” said Joe. “I would.”

“Four of those round rolls,” Sam told the girl behind the counter as confidently as a rich man.

Then he handed two of the rolls to Joe. “I’ll treat you today, but tomorrow it’s your turn. See. A little money in your pocket makes you feel like Rockefeller and who did we hurt? Some rich man who has lots of money? Some rich man whose belly is full? Nah. He won’t miss the money for a minute.”

Joe bit into the roll. It tasted warm and buttery, but no matter how good it tasted, Joe felt an ache in his stomach when he thought of lifting a wallet from a man’s pocket.

“Come on,” said Sam, as if reading Joe’s mind. “You’ll see it’s easy once you give it a try, but wait till tomor row. Tomorrow we’ll cross Brooklyn Bridge. Your eyes will pop out of your head when you see the bridge. It’s the most beautiful bridge in the world.”

“I’d better go b

ack to school tomorrow, Sam. Miss Williams will get suspicious if I’m out too many days. She might tell Aunt Sophie and then I’ll get in trouble.”

“Who cares if your dumb aunt is mad or that baby teacher is suspicious,”

said Sam impatiently. “Tell the teacher you were sick. You’re not too chicken to say that, are you?”

“No. I just can’t tomorrow,” Joe insisted.

Sam grunted and rolled his eyes. “So go back to that baby school. What do I care? You’ll soon be desperate to get out and have an adventure. Anyway, I need to see how Al is doing. He’s probably feeling much better by now and itching to make some real money. Al is one person who knows what’s what. Al is a real American.”

Chapter Ten

Sea Fever

Joe tried to shake off the memory of Sam’s sneering tone as he climbed the stairs to his apartment, He tried to forget how scared he felt being pushed off the rocks in the park and abandoned by Sam. He tried to think about what excuse he was going to give Miss Williams for missing two days of school. He knew he’d better think fast, but he was so tired from the day, his head felt like it was stuffed with rags. I’ll think of something in the morning, he decided.

But the next morning, as he waited for Miss Williams to call his name for attendance. His mind was as blank as the blackboard.

“Joseph Wisotsky,” she said in her soft, firm voice.

“Here,” said Joe.

“Where were you for the last two days?” she asked.

“I . . . I . . . was sick,” stammered Joe.

“You certainly look well today,” said Miss Williams, with a knowing look in hereyes. “Please see me at lunch.”

Oh no! thought Joe. She knows! Would she tell Anna? Would she tell Aunt Sophie? Would she send him to Mr. Cutler, the principal? Would Mr. Cutler smack his hand with a stick for misbehaving?

All through class Joe worried about Miss Williams, as he stood against the wall with Avram, glued to his side, at recess.

“Are you feeling better today?” Avram asked him. “Did you have a fever? Were you coughing? My sister has a fever and my mama is worried about her.”

Bee in Your Ear

Bee in Your Ear Avalanche!

Avalanche! Arctic Storm

Arctic Storm Queen of the Toilet Bowl

Queen of the Toilet Bowl Noodle Up Your Nose

Noodle Up Your Nose A Frog in My Throat

A Frog in My Throat Halifax Explodes!

Halifax Explodes! Dimples Delight

Dimples Delight Just Call Me Joe

Just Call Me Joe